(All text and images copyright Janet Green 2026, unless otherwise noted.)

Have you ever looked closely at a piece of Johnson Brothers Old Britain Castles dinnerware and become curious to learn more about Blarney, Cambridge, or Stafford Castle? If so, then you’ve experienced the hidden super-power of classic transferware!

In the early 19th century, British potteries began producing large quantities of illustrative transferware aimed at a growing American market. The pieces produced by Clews, Ridgway, Enoch Wood, Johnson Brothers (pre-Castles), and others depicted American pastoral landscapes, architectural scenes of New York and other cities, river scenes, and natural wonders such as Niagara Falls.

These dishes were affordable and beautiful, and the designs subtly served as visual history lessons at a time when books were expensive and literacy was not universal. Dinnerware could literally show Americans what their country looked like beyond their front door, and build a sense of national identity through depictions of events, landscapes, and architecture.

In her collector’s volume The Blue China Book, first published in 1916, Ada Walker Camehl states “… this group of English pottery is not only a valuable record of the American country and cities as they appeared a century ago, but is at the same time a surprisingly complete history of the first three centuries of our national life.”

As it turned out, Americans – who at the time still believed that superior pottery came from England – were eager to snap up these pieces, seamlessly blending history into domestic life. For transferware at this time was not relegated to display cabinets – it was handled, washed, stacked, and used daily. Through repetitive use, the imagery of transferware became part of our collective conversations and knowledge.

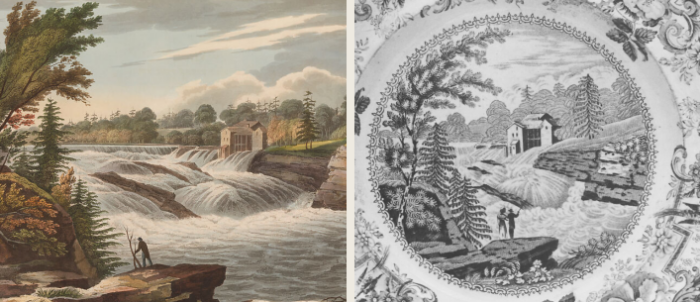

What’s interesting about the images themselves is that, for the most part, they were created by illustrators working from pictures by established, “published” artists. While a few potteries sent their staff artists “across the pond” to make their own sketches, more often they worked from existing paintings, prints, and even sketches from the notebooks of returning English tourists.

For example, the Irish-born artist William Guy Wall is one of the most influential figures for American-view scenic transferware. His successful print series known as the Hudson River Port Folio was eagerly adapted by English potters. These pictures depicted scenes of a naturally beautiful but culturally refined America, where nature coexisted peacefully with civilization. Educated in European artistic traditions, Wall created carefully balanced compositions showing that America had landscapes equal to those in Europe, believing that they deserved to be seen and remembered. Wall wasn’t just painting scenery – he was stylizing, editing, and curating his pictures to depict how America wanted to see itself and how it wanted to be seen by the world. Because of the established popularity of the pictures from the Port Folio, pottery depicting these images was practically guaranteed to be successful on the commercial market. Thus, many Staffordshire plates trace their origins directly to Wall’s compositions.

Additionally, although they depicted American subjects, the wares were engraved and produced in England. As a result, early American history was filtered through British artistic conventions and romantic ideals.

These additional filters, or layers of interpretation, explain why American buildings sometimes appeared slightly altered, landscapes were softened or felt grander than reality, and proportions leaned toward the English Picturesque style. These visual choices reveal not only what was depicted, but literally how history was framed for consumption. The dinnerware did not merely reflect culture; it actively participated in shaping it.

Despite the English artistic influence imposed upon American scenes, Camehl nonetheless concludes in her book that “So thoroughly did the early nineteenth-century artists perform their task of securing sketches of American scenery… that it is quite possible by means of the decoration… to enable the student of our early history to make a fairly complete tour of the land, and to look upon it as it appeared a century ago.”

By the early 20th century, as American tastes changed, the educational direction of transferware had also shifted: English potters began introducing American consumers to British history and heritage. One of the most beloved examples is the afore-mentioned Old Britain Castles by Johnson Brothers introduced around 1930 and still widely collected today, almost 100 years later. These scenes of castles, abbeys, and ancient ruins invited American buyers to romanticize Britain’s deep past.

Beyond Old Britain Castles, English potteries produced many transferware patterns aimed at American buyers that showcased other British architecture, landmarks, and scenery. Johnson Brothers itself also produced the Old Britain series, featuring cathedrals, manor houses, bridges, and rural landscapes. Their Coaching Scenes series featured historic coaching inns and roadside taverns.

Additionally, potteries such as Enoch Wood, Ridgway, Davenport, Clews and Wedgwood produced designs focused on historic British homes, landscapes, and architecture. These designs traded themes of American patriotism and identity-building for the romance, ancestry, and allure of the Old World – qualities that resonated strongly in U.S. homes from the late 19th century onward. They taught British geography and architectural history through repeated daily use, much as earlier wares had done with American themes.

Another more modern example of transferware that educates – or at least ignites curiosity – would be Royal China’s Currier and Ives. Introduced in 1949, this American-made pattern was beloved by mid-century homemakers and families for over four decades. The scenes depicted on the dinnerware were taken directly from commercially successful prints produced by American lithographers Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives from 1835-1907. These prints, popular and affordable in their time, depicted romanticized scenes of American farm life, historical events, and other subject matter. Prints chosen for the dinnerware line included The Homestead in Winter, The Old Grist Mill, The Rocky Mountains, Maple Sugaring, and others.

I think it’s probable that English and American potteries did not intentionally set out to educate anyone – I doubt we’ll ever unearth an upper-management memorandum directing the marketing department to find a way to teach history through dinnerware! These companies were, first and foremost, commercial ventures with the end goal of making money. They studied the American market, and produced products they believed would sell. By carefully choosing images that spoke to the American desire to evolve a national identity (and later, to a sense of collective American nostalgia), and by putting these images on something as ubiquitous as dinnerplates, the potteries unwittingly became visual historians. Ultimately, they had an unintentional but very real educational impact.

What collectors hold today, in antique and vintage transferware, is not a photographic record of the past, but a carefully edited artistic vision of it. For tablescapers, this adds another layer of meaning. When you place an American-view transferware plate on the table, you are sharing not just a scene, but an artist’s interpretation of a young nation filtered through British/European (and later, nostalgic American) eyes.

Furthermore, mixing American-themed transferware with British scenic patterns creates a table that reflects a transatlantic conversation about mutually appreciated and interpreted history.

By collecting and using transferware, we are not just preserving beautiful useful objects. We are curating fragments of cultural education that was delivered without books and in the most family-centric way possible: around the dinner table. By bringing these pieces back to the table through present-day tablescaping, we’re allowing history to once again take pride-of-place, and reclaim its seat beside us.

Here’s an image to Pin in case you’d like to save this post for future reference!

A note about using antique or vintage dinnerware: Many antique and vintage dinnerware pieces were produced before modern food-safety standards were established. As a result, some may contain lead, cadmium, or other materials that can leach into food and beverages, particularly when used with acidic or hot foods. While lead leaching does not cause immediate ill effects, repeated exposure over months or years may cause eventual health issues. Children and pregnant women should not consume food from dinnerware that is not certified as food-safe. Do your own research so you can make informed decisions for yourself, your family, and your guests about whether to actually use older dinnerware.